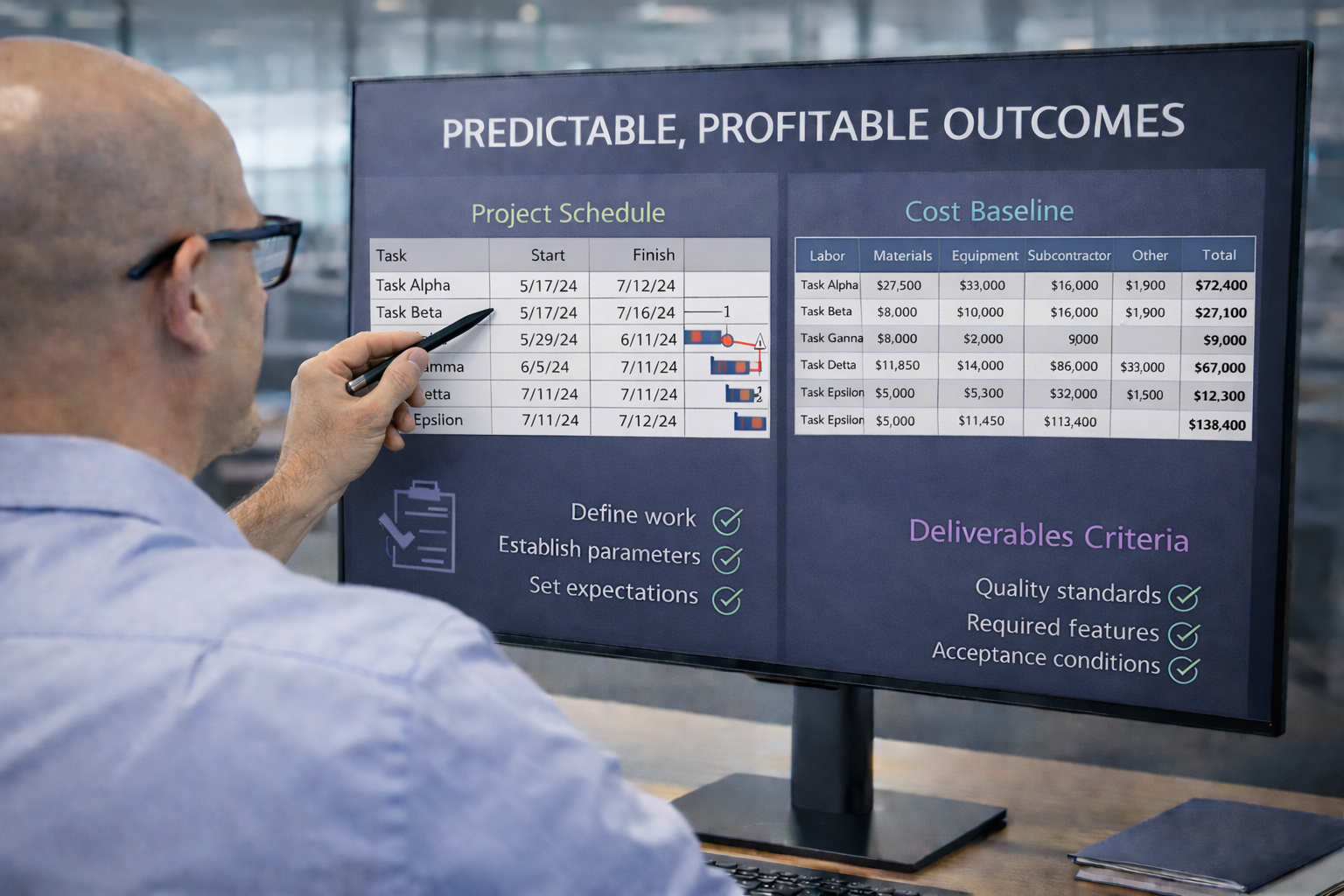

Predictable, Profitable, Outcomes:

Make Delivery Dates, Estimate at Completion, and Margins Boringly Reliable

The Goal Is Simple

Leadership should be able to ask four questions at any time and get the same answer every time:

- When will we finish?

- What is the estimate at completion (EAC)?

- What happens to margin and value?

- What is the next gate, and are we actually ready?

If the answers change every week, or depend on who you ask, you do not have a delivery system. You have activity.

This article describes the minimum planning and control mechanics required to make those answers boringly reliable.

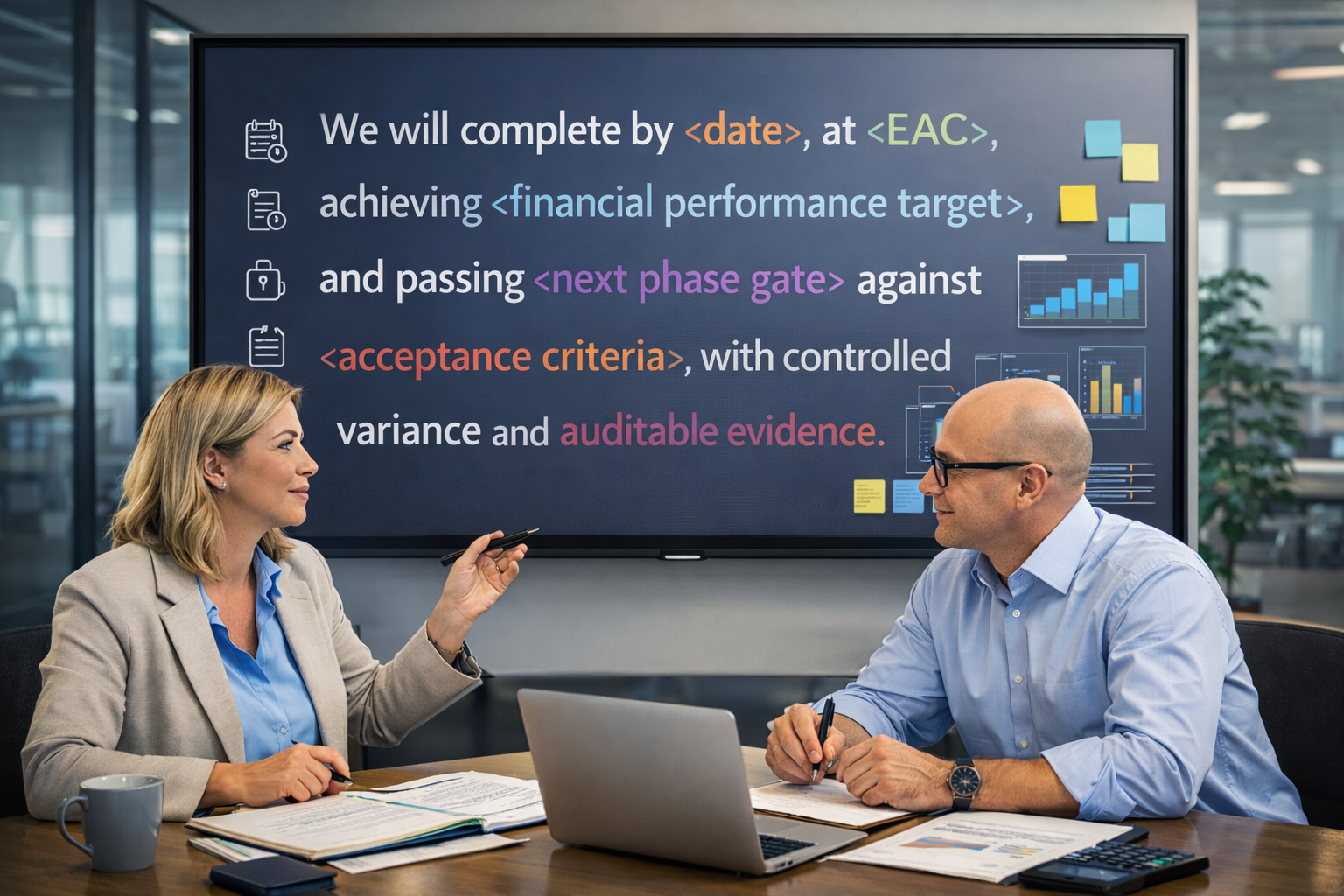

The One Sentence That Prevents Surprises

Before you build anything, write the definition of success as a measurable statement. This is not paperwork. It is the control statement the project runs on.

The Project Manager (PM) and Project Controller (PC) co-author it because it anchors the schedule baseline and forecast, estimate at completion (EAC), and financial performance targets. Engineering, Contracts, Quality, Configuration Control, Procurement, Documentation, Training, Finance, Operations, Supply Chain, and Manufacturing review and sign off on the parts they own. Once approved, it becomes the reference for phase gates, change control, reporting, and corrective action.

We will complete by <date>, at <EAC>, achieving <financial performance target>, and passing <next phase gate> against <acceptance criteria>, with controlled variance and auditable evidence.

This definition is created during initiation and early planning, approved with the scope, schedule, and cost baselines, and updated only through integrated change control.

What Boringly Reliable Actually Means

Define reliability numerically and manage to it. Stop managing delivery with vibes and color charts. Pick a small set of numbers that define reliable execution and keep them inside agreed tolerances.

Reliability is not subjective confidence. It is controlled, repeatable behavior in schedule and financial forecasts. Define that behavior with metrics and tolerances, review them on cadence, and execute corrective actions when performance drifts.

Establish A Reliable Baseline

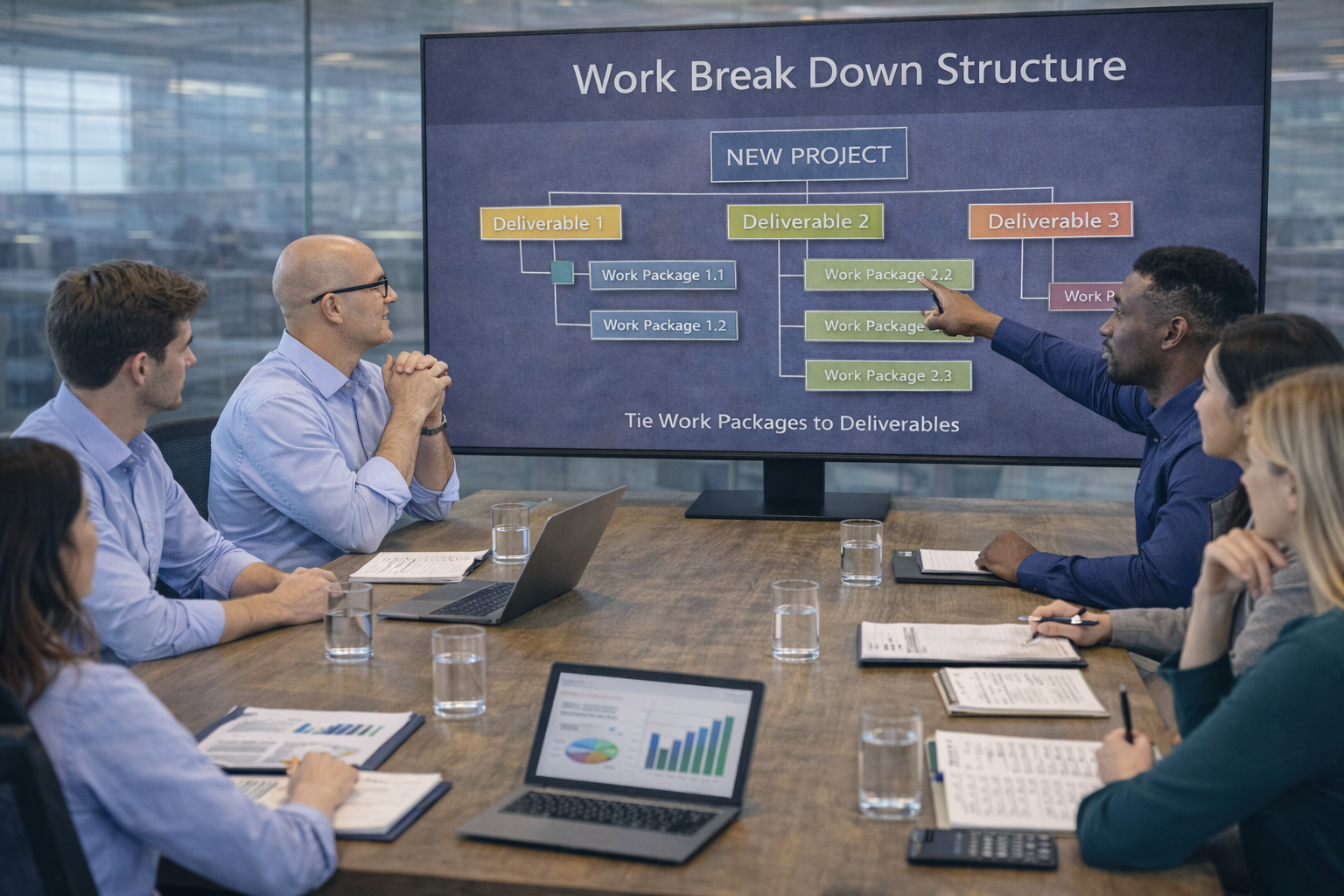

Build a work breakdown structure (WBS) that can be managed

Build a work breakdown structure (WBS) that can be managed. Decompose work until accountability is clear and progress can be verified. Tie work packages to deliverables and acceptance criteria. The WBS is your scope foundation, not a documentation artifact. Start by decomposing the project into deliverables, not activities. Break each deliverable down until a single owner can be held accountable and progress can be measured objectively. Stop decomposing when you can define clear entry and exit criteria and required acceptance evidence. Assign each work package an owner, budget, and schedule tie point so it can be planned and tracked. Treat the WBS as the backbone of planning and control.

WBS Reality Check

- Can every work package name a single accountable owner?

- Can progress be verified without asking for opinions?

- Can forecast and cost impacts be traced to a specific work package?

- If a work package slips, do you know which gate and deliverable it affects?

Define scope boundaries explicitly

Document what is in scope in plain language tied to deliverables and outcomes, and explicitly list what is out of scope so it cannot enter later through urgency or assumptions. Capture assumptions that affect scope, such as customer-furnished items, site readiness, or reuse of existing designs. Review boundaries with stakeholders to confirm shared understanding and ownership. Use scope boundaries as the first filter for change requests.

Scope Boundary Test

- Is this request already covered by an existing deliverable and acceptance criteria?

- Is it explicitly in scope, or is it trying to sneak in through an assumption?

- If it is out of scope, what is being traded (schedule, cost, or another deliverable)?

- Does it change the customer acceptance event, contract milestone, or configuration baseline?

- Has a change request been written with impacts to scope, schedule, cost, risk, and benefits?

If it is not in the scope boundary statement, it is not work until it is approved through integrated change control.

Establish acceptance criteria for deliverables

Define the evidence required for acceptance (test reports, inspection results, approved documentation, training sign-offs). Set acceptance criteria when the deliverable is defined, not at the end of execution. Make criteria objective and binary so there is no debate at handoff. Assign who produces the evidence and who approves it. Use acceptance criteria to drive planning, scheduling, and progress measurement.

Definition Of Done (minimum standard)

- Accepted when (one sentence that is pass or fail)

- Evidence required (the exact artifacts, i.e., test report ID, inspection record, approved document revision, training roster)

- Approver (the single role that signs acceptance, i.e., customer, Quality, Engineering authority, Operations)

- Where stored (the repository location and naming convention)

- Rejection rule (what constitutes “not accepted” and what happens next, i.e., rework, retest, resubmit)

Build An Executable Schedule Baseline

Develop an integrated project schedule that reflects reality

Start by building the schedule from the work breakdown structure (WBS), not a generic template. Link engineering outputs to downstream procurement, build, test, documentation, logistics, and acceptance activities so handoffs are explicit. Use actual supplier lead times, review cycles, and resource constraints rather than optimistic placeholders. Include verification, rework, and approval steps, not just the idealized path. Validate logic and sequencing with functional owners to confirm the schedule reflects how work is actually performed.

Schedule Reality Check (before baseline approval)

- Are engineering deliverables explicitly linked to procurement, build, test, and acceptance, or are they just dated milestones?

- Are supplier lead times and review cycle times based on actual data and current capacity, not best case?

- Are verification, approvals, and rework explicitly scheduled, with owners, or assumed to “fit in”?

- Does every external dependency have an owner and a due date for the input, not just the output?

- If one activity slips, does the impact propagate through logic to the critical path, or does the finish date stay unchanged?

If the schedule cannot propagate a slip, it is not a model of reality, it is a presentation.

Identify the critical path and the phase gates that matter

The critical path is the sequence of logically linked activities that determines the earliest possible project completion date; any delay on this path directly delays the finish. Phase gates are formal decision points in the schedule where defined entry and exit criteria must be met, with objective evidence, before work is authorized to proceed to the next phase. Calculate the critical path using fully linked logic so it reflects real dependencies, not imposed dates. Identify the few phase gates that truly control risk, quality, and acceptance, and model them as zero-float milestones or constrained activities. Make gate entry and exit criteria visible in the schedule by tying them to specific deliverables and evidence-producing tasks. Review the critical path and gate logic with the team to confirm what drives the finish date, and use the critical path to focus recovery actions, not to defend the schedule.

Critical Path and Gate Test (use this to validate the schedule)

- If a critical-path activity slips by 5 working days, does the finish date move automatically based on logic, or does nothing change?

- Are the critical-path activities real work with owners and evidence, or are they placeholders and summary tasks?

- Are phase gates tied to specific deliverables and required evidence, or are they just dated milestones?

- If a gate fails, is there a defined rule that forces replan, forecast update, and integrated change control when dates or scope move?

- Can each Functional Lead point to the gate evidence they own and when it will be produced?

If the critical path is not driven by logic and evidence, it is not a critical path, it is a guess.

Align schedule milestones with contractual commitments and customer acceptance events

Map contractual milestones and customer acceptance events into the schedule as external commitments. Link internal completion, test, documentation, and readiness tasks to those milestones so there is no hidden work after internal completion. Ensure milestone dates reflect the full acceptance process, including reviews, inspections, and approvals. Reconcile any misalignment between contract dates and realistic execution early, before baseline approval. Use these milestones as governance checkpoints, not just reporting dates.

Contract Milestone Reality Check (before you baseline the schedule)

- Is each contractual milestone tied to the exact acceptance event that triggers payment or formal customer sign-off?

- Are documentation approvals, inspections, test reports, and training sign-offs explicitly linked as predecessors, or assumed?

- Is there a named owner for every acceptance artifact and review cycle, including customer review time?

- Can you point to the last internal task that must finish before the milestone, with evidence required?

- If the milestone slips, do you know the contract impact (liquidated damages, revenue timing, holdbacks, award fee)?

If the milestone is not tied to acceptance evidence, it is a date on a chart, not a commitment you can manage.

Build An Executable Cost Baseline

Document the basis of estimate (BOE) and assumptions

Hidden assumptions produce surprise overruns. Document how each major cost element was estimated, including labor hours, material quantities, rates, and external inputs. Explicitly list the assumptions that make the estimate valid, such as productivity rates, reuse of designs, supplier lead times, or customer-provided items, and tie them to specific work packages so impacts are traceable. Review assumptions with Engineering, Procurement, and Finance to confirm they are realistic and current. When an assumption changes, require a forecast update and route the impact through integrated change control.

BOE Assumption Control (minimum standard)

- List the top 10 assumptions that drive cost and schedule (labor rates, productivity, supplier lead times, customer-furnished items, reuse).

- For each assumption, assign an owner and a verification date (when it will be confirmed or revalidated).

- Define a trigger that forces action (for example: supplier lead time changes by more than X days, labor rate change, design reuse not approved).

- Require that every forecast cycle answers one question: Which assumptions changed, and what is the cost, schedule, and margin impact?

- If an assumption breaks, treat it as a governance event: update estimate to complete (ETC), estimate at completion (EAC), schedule forecast, and process through integrated change control if baselines move.

If an assumption is not owned, time-bound, and trigger-based, it is not an assumption, it is a hidden risk.

Allocate resources and budgets to measurable work

Assign budgets and resources at the work package level with a single accountable owner. Time phase the budget to the schedule so variance appears when work moves. Avoid lump-sum allocations. Use this structure to compare planned, earned, and actual performance.

If it is real, it looks like this

- Work package: “Factory Acceptance Test complete”

- Owner: Test Lead

- Budget: 240 labor hours plus $8,000 test materials

- Earn rule: 0/100 at signed test report (Report ID ___)

- Forecast signal: if the test procedure approval slips 5 days, the work package finish and estimate at completion (EAC) move in the same reporting cycle

Control Account Test

- One owner, one budget, one output: One accountable role, one cost bucket, one measurable deliverable with defined acceptance evidence.

- Variance explainable in one sentence: State the driver, the impact, and the corrective action (what moved, why, what fixes it).

- Slips show up immediately in forecast: Logic-driven schedule and time-phased budget update the forecast in the same reporting cycle, not at month end.

If a work package cannot produce an immediate, explainable variance tied to an owner, it is not a control account and should not be budgeted.

Define measurement rules so progress is not subjective

Establish clear earning rules for each work package before execution begins. Define how progress is credited, such as 0/100, weighted milestones, units accepted, or test pass criteria, and require objective evidence for each. Prevent double counting by assigning each deliverable to one work package and one earning method. Apply the same rules consistently across reporting periods. Do not allow percent complete to be based on effort or opinion - no evidence, no credit.

Earning Rule Standard (minimum, enforceable)

- Every work package must declare one earning method (0/100, weighted milestones, units accepted, or test pass) before baseline approval.

- Every earning event must name the evidence artifact (test report number, inspection record, approved document revision, signed checklist) and the approver.

- No evidence, no credit is enforced weekly, not at month end.

- One deliverable belongs to one work package and earns value once - no parallel credit in multiple places.

- Any change to earning rules requires governance approval because it changes reported performance.

- Evidence standard: The evidence artifact must be uniquely identifiable (ID, revision, date) and stored in the agreed repository so anyone can audit it.

- Enforcement rule: No artifact, no credit. No credit, no earned value. No earned value, no forecast.

If progress cannot be proven, it cannot be earned or forecast.

Key Takeaway

Predictable delivery is not culture or effort. It is designed through baselines, evidence, cadence, and discipline. When these mechanics exist, outcomes become boring. That is the goal.

Here is what separates “we are sort of doing it” from reliable control, and how it maps to the operating mechanics in this article:

- Baselines and forecasting: Reliable teams update schedule forecast and estimate at completion (EAC) quickly when performance changes, using the baseline as the anchor for variance and forecasting.

- Evidence and acceptance: Progress is credited only with objective evidence, consistent with acceptance criteria, Definition of Done, and earning rules, so “no evidence, no credit” is enforceable.

- Governed change: Scope and assumptions do not drift through side doors. Changes move through one governed path with impact analysis and integrated change control.

- Behavior under pressure: The system holds when pressure shows up. Schedules do not become presentations, gates do not weaken, and “green” does not survive critical path slips.

- Executive accountability: Leadership protects the rules of the system, so teams do not have to negotiate reality every week.

Most organizations already do parts of this. The difference between “we have baselines and documents” and “we have control” is whether the system still holds when pressure shows up: a late supplier, a slipped design, a customer change, a gate miss, or a margin hit. Reliability is proven in those moments by three behaviors: forecasts update quickly, progress is credited only with objective evidence, and changes move through one governed path.

What leaders must protect: one plan, one set of baselines, one change path, and one evidence standard. If leadership allows side doors, exceptions, and “we will clean it up later,” predictability is gone by design.

When leadership protects the system, teams stop negotiating reality, bad news arrives early and actionable, and delivery becomes repeatable instead of heroic. That is the win: calmer execution, credible forecasts, and margins that do not erode quietly in the background.

This is not more paperwork; it is fewer surprises, fewer rework cycles, and fewer late escalations, because reality is measured once and governed consistently.