Evidence Return:

How Contractors Deliver Flowdown-Compliant Work That Gets Accepted

Introduction

Managing flowdowns is not paperwork. It is execution. If you are a contractor or subcontractor, the customer’s flowdowns are not “contract language.” They are requirements you must translate into your internal work system, plan, schedule, budget, execute, verify, and close with objective evidence.

The hard truth is simple. Benefits, innovation, and schedule heroics do not matter if the customer cannot accept the deliverable. Compliance is not a supporting activity. Compliance is a deliverable. Evidence return is how you prove it.

This article is written for the people who win the work and the people who must deliver it: Sales and Business Development, Project Managers, Project Controllers, Engineering leaders, Contracts, Quality, Configuration Control, Procurement, Documentation, Training, Finance, and Logistics. If you want predictable acceptance and predictable cash, you need a controlled system that makes flowdown compliance executable, visible, and provable.

Supplier Reality Check: What “100% Compliant” Actually Means

Most teams say, “we will comply.” That is not a plan. “100% compliant” has an operational definition:

- Every flowed requirement is identified, interpreted, planned, assigned, verified, and proven. This is how you turn “we’ll comply” into controlled execution that Sales can defend and the PMO can forecast. When you do this, requirements stop hiding in contract language and start living as owned work with due dates and acceptance criteria. It prevents the classic late-stage surprise where a clause gets discovered after build, after ship, or during customer acceptance. The benefit is predictable delivery and fewer internal fights, because ownership and verification are decided up front. It also protects margin by avoiding unplanned rework, expedited documentation, and schedule recovery costs. When this discipline is in place, compliance becomes measurable progress instead of last-minute heroics. If you skip it, you will eventually pay for it in rejected deliverables, delayed acceptance, and customer distrust.

- “Done” equals deliverable + objective evidence, tied to as-built or as-performed reality. This is what gets you accepted and paid without negotiation at the finish line. It forces the team to build the evidence package as the work happens, not assemble it from memory after the fact. The benefit is faster acceptance cycles because reviewers see complete, traceable proof that matches the delivered configuration or performed service. It also reduces audit exposure and warranty disputes because the records tie cleanly to the exact unit, version, or work order. When done right, Finance invoices against accepted milestones with confidence, not hope. If you treat “done” as shipment or completion alone, you invite stop-ship calls, conditional acceptance, and payment holds. In the worst case, you deliver a perfectly good product or service that cannot be accepted because the proof is missing or does not match reality.

- No silent substitutions. No undocumented deviations. No missing records. No late surprises. This is how you keep configuration integrity, protect verification validity, and avoid requalification chaos. The benefit is stability: engineering assumptions hold, quality evidence stays defensible, and the customer sees a clean chain from requirement to delivered outcome. It prevents the supplier-side trap of “optimizing” locally and then trying to paper it over at delivery. When changes are controlled and documented, approvals happen before impact, not after damage. This protects schedule credibility because surprises are what blow forecasts and force resequencing. If you allow silent change or incomplete records, you create acceptance disputes, corrective action churn, and the risk of having to rebuild your evidence trail under pressure. The consequence is simple: you lose leverage late, and late is the most expensive time to negotiate compliance.

If you cannot prove compliance with objective evidence, you are not compliant. You are hoping the customer accepts your narrative.

Scope includes requirements, quality includes conformance and verification, procurement governs seller deliverables and acceptance, and benefits are realized only when deliverables are accepted and usable. From a PMBOK perspective, compliance must be planned and managed through scope, quality, and procurement controls because acceptance is the gateway to intended benefits.

Flowdown Intake and Analysis: Turn Customer Clauses into Executable Requirements

This is the supplier-side equivalent of a requirements workshop, consistent with PMBOK discipline to collect requirements, define scope, and plan quality and procurement up front. If you skip it, you will run discovery during execution, which is the most expensive time to learn what ‘required’ really means.

Flowdown Analysis Workflow

Intake sources:

- Prime contract excerpts (as provided to you), SOW, terms and conditions

- Quality notes, inspection and acceptance language

- CDRLs or data item requirements

- Cybersecurity obligations and incident reporting

- Export and controlled technical data handling (ITAR/EAR if applicable)

- Data rights and markings requirements

- Configuration control and change authorization requirements

Now break each flowdown into executable components. For each flowed requirement, capture:

- Requirement statement: rewrite into plain-language “supplier shall” language

- Applicability: what work packages, locations, systems, and data types are in scope

- Verification method: inspect, test, review, audit, demonstrate

- Evidence artifact: what proof is required, in what format, who signs, and when it is due

- Acceptance owner: customer role if known, plus your internal acceptance authority

- Internal owner: a named person accountable for producing the evidence

- Triggers and risks: what causes drift, and what happens if performance slips

- Status: not started, in work, submitted, approved, closed

- Link to proof: direct references to the actual evidence (test report, cert, traveler, approvals)

- Linkages: RFI/clarification ID, assumption ID, change-control item, risk ID

Deliverable: The Flowdown Compliance Register (FCR)

The FCR is a version-controlled register (often a spreadsheet or database) that maps each flowed requirement to an owner, verification method, required evidence artifact, approver, due date, and current status, with links to the proof. Treat it like configuration: control revisions, maintain an audit trail, and use it as the single source of truth for compliance reporting and acceptance readiness.

Customer Concurrence and Baselining

Do not treat the FCR as an internal spreadsheet. Baseline it at award as FCR Rev 1.0 and push for customer concurrence on the parts that define “done”: the plain-language requirement interpretation, verification method, required evidence artifacts, approvers, and timing. If the customer will not approve the full register, get explicit approval of the Evidence Return checklist and the high-risk flowdowns (cyber, export, data rights, special test and inspection hold points). Then contract-link the baseline: reference it in kickoff minutes, attach it as a controlled exhibit, or cross-reference it in the deliverables list so it carries weight. From that point forward, treat changes to clauses, acceptance criteria, evidence formats, or approval steps as controlled changes to the baseline. When new obligations show up, the FCR becomes your audit trail and your change-order backbone: you can point to the baseline requirement, show what changed, and quantify the cost, schedule, and documentation impact for equitable adjustment.

Ambiguity: Kill It Early Or It Kills You Later

Most supplier compliance failures are not technical. They are ambiguity plus schedule pressure.

Rules For Ambiguity

- If it cannot be verified objectively, it is ambiguous. If you cannot point to a measurable pass-fail check, a defined test, or a specific record that proves compliance, you do not have an enforceable requirement. Lock down the verification method and the acceptance criteria in writing before you execute.

- If evidence format, approver, timing, or criteria are missing, it is ambiguous. If the customer has not stated what the evidence looks like, who signs it, when it is due, and what makes it acceptable, you are guessing. Force closure by proposing the evidence artifact, naming the approver, and tying it to a milestone or gate.

- If it conflicts with another requirement, it is ambiguous. Conflicts create no-win delivery scenarios, where meeting one obligation violates another. Document the conflict, request a single controlling requirement, and do not proceed on assumptions.

Supplier Actions

- Issue a formal question: RFI, clarification request, or contract query. State the exact clause or requirement reference and quote only what is necessary to anchor the question. Describe the ambiguity in operational terms: what you cannot verify, what evidence is undefined, or what conflicts. Ask a closed-ended question that forces a decision, preferably with A/B/C answer options, and include your recommended answer if you have one. Route it to the authorized contracting authority (or the designated technical authority if the contract allows), copy the customer PM, and set a response due date tied to the schedule gate the answer affects. Track it in a log with owner, status, impact, and a clear no-response rule so it cannot disappear in email.

- Propose your interpretation in writing and request explicit approval. Write your plain-language “supplier shall” interpretation and the acceptance criteria you will use. Define the verification method and the exact evidence artifact you will deliver, including format, approver, and timing, and attach a template or sample so the customer approves what they will actually receive. State the consequence if the customer disagrees later, such as rework, schedule slip, or change request, so the decision is informed. Request written approval from the customer’s authorized representative, not just a hallway nod, and include a one-line approval statement such as “Approved as written” or “Approved with attached edits.” Do not start irreversible work until you have that approval or documented interim direction that is captured and traceable.

- Document assumptions in the FCR and tie them to change control. Add an “Assumption/Interpretation” field in the FCR entry for the flowdown and record the date, author, and the customer contact tied to it, with a link to the source record (RFI ID, email, or meeting minutes). Tag it as “pending customer approval” if it is not yet approved, assign an owner, and treat it as a risk until it is closed. Link the assumption to the specific deliverables, verification steps, and evidence artifacts it drives, and classify its impact on cost, schedule, and compliance exposure. If the assumption changes, open a change item and run impact analysis on scope, cost, schedule, and evidence package effects. Update the FCR version, assign an expiry date or gate for closure, and maintain an audit trail so you can prove what was assumed, when, and why.

Change Management: Flowdowns Change and Uncontrolled Change Is Noncompliance

From the supplier side, the most common failure mode is simple: new obligation, no schedule, no money, and no formal change. Teams try to absorb it quietly. When you absorb changes silently, you create hidden scope, hidden risk, and late failures. That is how margin dies and compliance collapses.

Flowdown Change Control

- Baseline the FCR at award: Version 1.0. Publish FCR Rev 1.0 immediately after award and treat it as the “as-awarded” compliance baseline. Freeze the fields that define acceptance: requirement interpretation, verification method, evidence artifact, approver, and due date. Put it under document control with version history and controlled access so edits do not happen in email. Assign a single FCR owner (PMO, Contracts, or Quality) who is the only person allowed to release a new revision. Distribute the baseline to all internal owners and sub-tier managers so everyone is executing to the same definition of “done.”

- Treat any new clause, revised acceptance criteria, new evidence format, or new approval step as a change. If it changes what you must deliver, how you prove it, who must approve it, or when it can be accepted and invoiced, it is not “clarification,” it is scope change. Require every customer direction to be mapped to an FCR line item, even if the conclusion is “no impact.” When a change is proposed, log it as an FCR revision entry showing old versus new and the affected work packages and milestones. Do not implement until it is approved through the change process or you have documented interim direction. Use one test: will this change acceptance or invoice eligibility.

- Run impact analysis. For any change, assess the effect on scope, cost, schedule, resources, tooling, training, logistics, documentation volume, and sub-tier flowdowns. Start with the impacted FCR line items and list the new work created: tasks, artifacts, reviews, inspections, approvals, and re-test or re-qualification if applicable. Quantify the delta in real terms: added labor hours by function, added test or inspection time, added review cycles, added artifacts, added travel or source inspection, added lead time, and added risk to the critical path. Update the schedule with new dependencies and flag “no-ship” and “no-invoice” gate impacts. Summarize the result in a one-page impact statement Sales, PMO, and Contracts can use immediately.

- Submit a formal change request when required; do not absorb silently. Put it in writing with the contract reference, the FCR baseline reference, and the impact summary, and tie it to equitable adjustment and/or revised dates. State what work will pause if approval is delayed, because vague changes turn into schedule traps. Route it through the customer’s authorized channel and track it like any other deliverable until it is closed. If you proceed under interim direction, document that it is provisional and keep the change open until formally settled. If it is not settled, you did not protect margin, and you did not protect compliance.

Integrated change control is not bureaucracy. It is protection. It preserves traceability between what was contracted, what is executed, and what is accepted. From a PMBOK perspective, Integrated Change Control is the backbone of compliance.

Ownership: Every Flowdown Has A Named Accountable Owner

Avoid “everyone owns compliance,” which means nobody does. Ownership is how you turn requirements into closure.

What “One Owner Per Flowdown” Means

A “flowdown line item” is one discrete record in the FCR. One line item equals one manageable obligation with a defined verification method and a defined evidence artifact. If you cannot point to the specific row in the FCR, you do not have real ownership

How To Structure The FCR For Ownership

Each FCR line item must answer four questions without hand-waving:

- What is the requirement in plain language?

- How will it be verified? What evidence artifact proves it.

- Who is accountable for producing that evidence and getting it accepted?

- If any of those are unclear, the item is not ready for execution.

Break Complex Clauses into Executable Items

Many clauses contain multiple obligations, especially in cybersecurity, data rights, quality systems, reporting, records retention, and export handling. Do not assign one clause to one owner if the clause contains multiple deliverables and proof types. Split it into multiple FCR line items so each obligation has a single accountable owner and a clear evidence artifact.

Accountable Does Not Mean “Does All The Work”

One accountable owner does not mean one person produces every record or performs every verification step. It means one person is on the hook to drive the obligation to closure, coordinate contributors, clear blockers, and deliver acceptance-ready proof. Supporting roles are still defined by the RACI, but accountability is single-threaded, so nothing hides in handoffs.

Ownership Model

- One accountable owner per FCR line item. Assign a named person to each row in the Flowdown Compliance Register, not a department. That owner is responsible for driving the requirement to closure, clearing blockers, and delivering acceptance-ready proof by the gate date. If a row has two owners, it has zero owners and it will surface late as a surprise.

- Supporting roles defined (RACI). For each FCR line item, define who produces the artifact, who reviews it, who approves it, and who needs to be informed. Put the RACI in the same record or directly linked so it cannot drift from the requirement. If the RACI lives in a separate slide deck, it will be ignored when pressure hits.

- Owners must have authority to produce evidence, not just track it. The accountable owner must control the resources, access, and decisions required to generate the proof, or have a direct escalation path to someone who does. If the owner cannot enforce document control, gate entry criteria, and corrective action timing, they are a status reporter, not an owner. The consequence is predictable: you “know” you are at risk but you cannot change the outcome.

Example mapping: Export handling (Export Compliance), cyber evidence (InfoSec), inspection and test evidence (Quality + Engineering), configuration baseline (Configuration Control), data rights markings (Contracts + Documentation), invoice gating (Finance + PM).

Planning and Scheduling: Put Compliance Work in The Project Schedule - Not in Email

This is where most suppliers fail. They treat compliance as overhead, so it never gets resourced.

Turn Compliance into Scheduled Work

Add tasks for procedure approvals, traveler creation, inspection plan approval, first article and witness points, audits, document creation and reviews, training completion, and evidence package gate reviews. Tie them as dependencies to build, ship, install, and milestone billing. Put “no-ship/no-invoice” gates in the schedule.

Treat compliance as schedule logic, not a checklist. Build the IMS so evidence-producing work is hard predecessor logic to build, ship, install, and invoice, not parallel “admin” activity that gets squeezed when dates slip. Put formal gates in the plan (Before Build, Before Ship, Before Invoice, Before Closeout) with clear exit criteria tied to the evidence return checklist, and make the gate a stop sign, not a suggestion.

Schedule customer review and approval cycles as real activities with durations, because “waiting on customer” is still schedule risk that hits your cash. Include rework loops for rejected procedures, test reports, and data items, because rejection is normal and pretending otherwise is how you end up in end-game chaos. Assign named owners and load resources for every compliance deliverable, because un-resourced tasks are not tasks, they are wishes. Make “no-ship” and “no-invoice” constraints explicit so execution cannot outrun evidence and create the two outcomes you cannot afford: rejected acceptance and withheld payment.

Performance Reporting: Compliance Is Measurable

Give Sales, PMs, and Controllers a weekly dashboard that answers one question: are we on a path to acceptance and cash, or are we drifting into a documentation and approval trap. If the metrics do not drive decisions, they are noise

Who Owns It

The supplier Project Manager (or PMO Project Controls, where that role exists) publishes the dashboard and runs the internal compliance review. Each function owns the accuracy of its metrics, but reporting is single-threaded: one owner reports, many owners feed.

Data owners (inputs): Quality (NCR/SCAR, inspections, audits), Configuration Control (baselines, pending changes, deviations), Contracts/Subcontracts (RFIs, approvals, change requests), Documentation/CDRL owner (submittals and approvals), Engineering (procedures, test readiness, dispositions), Training/functional leads (training completion), and Finance (invoice eligibility and payment holds).

This does not have to become a weekly slide-deck factory. If you run it as a manual reporting exercise, it will crush people managing multiple projects. If you run it as a control system, it scales across a portfolio.

Make It Exception-Based, Not Report-Based

Default state is “green, no drama.” The meeting is about exceptions, not narration. Review only what is trending wrong or blocking a gate. Limit discussion to the top 5 exceptions: blocked gates, overdue approvals, evidence completion behind plan, aging NCR/SCAR, and pending configuration approvals.

Keep The Dataset Small and Standard

Do not build a custom dashboard per project. Use the same 10–12 KPIs everywhere so portfolio rollups are automatic and the team is not reinventing reporting.

Automate Collection Where It Matters

The PM should not be retyping status. Functional owners update their fields in the system, and the dashboard reads it. Pull metrics from tools you already have: FCR tracker, RFI log, QMS (NCR/SCAR), document control (CDRL status), configuration/change system, training LMS, and Finance/ERP. If it is not in a system, it will not scale.

Supplier Flowdown KPI Set

Leading indicators tell you you’re going to miss acceptance. Lagging indicators tell you that you already did. Run both but manage to the leading set.

- Evidence package completion vs plan (LEADING): predicts gate readiness, acceptance timing, and invoice eligibility.

- Open clarifications aging (LEADING): predicts late disputes and blocked gates if answers arrive after build or shipment.

- NCR aging (LEADING): rising aging predicts schedule slip and incomplete evidence trails.

- SCAR aging (LEADING): slow closure predicts repeat defects, audit exposure, and rework churn.

- Pending configuration changes awaiting approval (LEADING): predicts un-acceptance-ready product and requalification risk.

- Training completion for required roles (LEADING): predicts audit findings, handling violations, and rejected evidence.

- On-time CDRL/data item submittals (LEADING): predicts acceptance delays; track “approved” not just “submitted.”

- Customer review cycle time (LEADING): often the hidden critical path and hidden cash delay.

- Rejected deliverables for missing or incorrect evidence (LAGGING): acceptance failure signal; track early draft rejections as a leading trend.

- Stop-ship events (LAGGING): damage indicator; if you track “stop-ship triggers” and near-misses, those become leading.

- Payment holds due to documentation gaps (LAGGING): cash impact indicator; use forecasted hold risk as a leading measure.

- Audit findings and repeat findings (LAGGING): governance failure signal; use open finding aging as a leading control metric.

Cadence And Governance

Biweekly internal compliance review: review FCR status, top blockers, and action owners. Focus on gates at risk, not storytelling. Timebox it.

Monthly customer-facing compliance status: show evidence progress, approvals, and open clarifications tied to specific gates. Ask for decisions, not updates.

Gate reviews: Before Build, Before Ship, Before Invoice, Before Closeout. Each gate ends with pass, conditional pass with actions, or stop until corrected.

Exception rule: if a leading indicator crosses a threshold or a gate is at risk, escalate to the customer immediately. Do not wait for the monthly cadence.

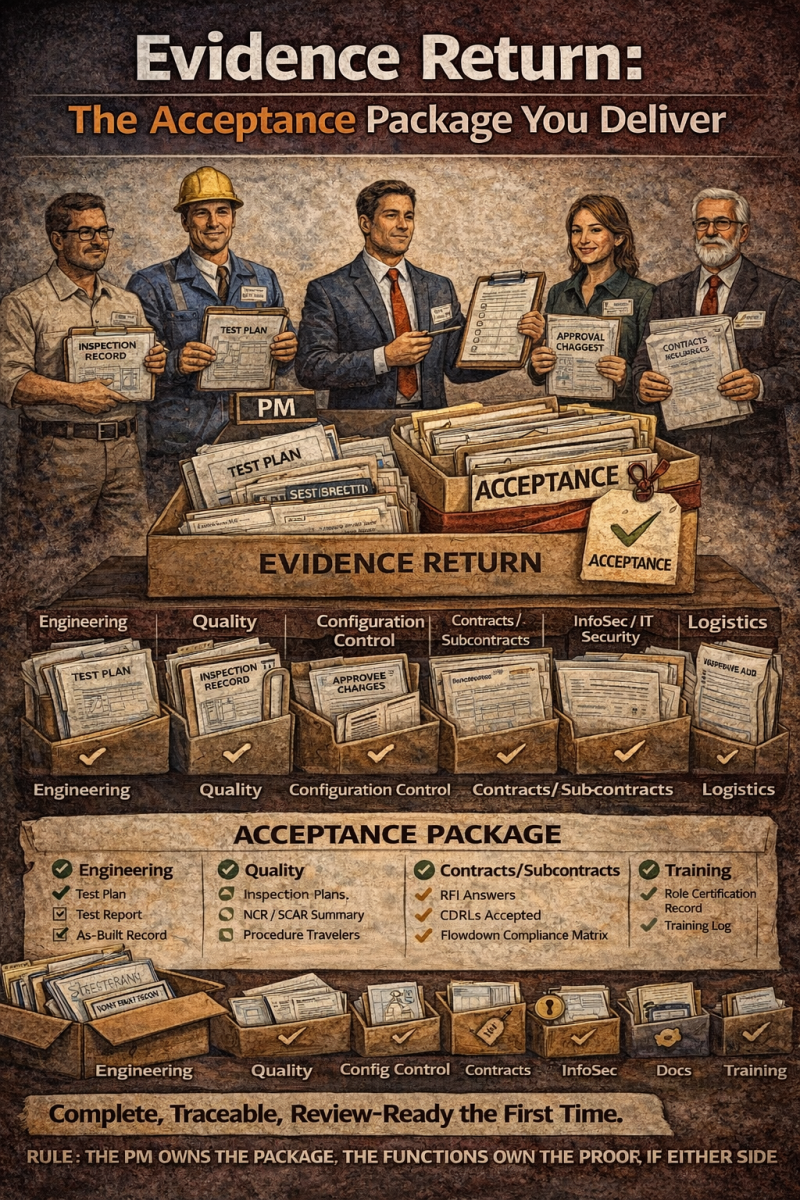

Evidence Return: The Acceptance Package You Deliver

Evidence return is your acceptance package. Treat it like a deliverable with its own requirements, owners, schedule logic, and gate criteria, not a documentation afterthought. Describe it like a product because that is how the customer will judge it: complete, traceable, and review-ready the first time. When the evidence return is clean, acceptance is predictable and invoices clear without negotiation. When it is sloppy or late, you get the worst outcome: a finished deliverable that cannot be accepted because proof is missing or does not match as-built or as-performed reality. One rule keeps you out of that trap: build the evidence package progressively through gates, not as a last-minute assembly job.

Ownership Model: One Package Owner, Many Artifact Owners

The Evidence Return package has one accountable owner: the supplier Project Manager. The PM is accountable for acceptance readiness, timing, and completeness because acceptance and invoicing run through the PM’s plan and gates. That does not mean the PM authors everything. Each artifact in the package has a functional owner who produces it, signs it, and keeps it audit-ready. The PM’s job is to make the work executable: assign owners, put the evidence work in the IMS, enforce gates, and prevent shipment or invoicing when the package is incomplete.

Distributed artifact ownership typically looks like this:

- Engineering: technical compliance narrative, test procedures, test reports, technical dispositions

- Quality: inspection plans, travelers, inspection records, NCR/SCAR status and closures, audit evidence

- Configuration Control: baselines, revision control, approved changes, as-built configuration record

- Contracts/Subcontracts: flowdown interpretations, RFIs, approvals, change requests, data rights terms

- Documentation: CDRL/SDRL packaging, formatting, submission control, records indexing and traceability links

- Training: training completion records for required roles and certifications

- Export Compliance: export classification, access controls, export logs, controlled-handling procedures

- InfoSec/IT Security: cyber attestations, incident reporting evidence, tool and environment approvals

- Finance: invoice gating, milestone acceptance references, payment hold tracking

- Logistics: packing/shipping records, chain-of-custody where applicable, delivery confirmations

Rule: The PM owns the package. The functions own the proof. If either side fails, acceptance fails.

Where CDRLs and SDRLs Fit

CDRLs (Contract Data Requirements List) and SDRLs (Supplier Data Requirements List) are usually the formal data deliverables list: what documents or data you must submit, in what format, and when. They are often major components of the evidence return, but evidence return is bigger than the list itself. A customer can require proof for acceptance that is not captured cleanly as a CDRL line item, and suppliers can fail acceptance by treating “data submittal” as the finish line instead of “acceptance-ready proof.”

Use this simple distinction: CDRLs and SDRLs define the contracted data deliverables. Evidence return is the acceptance package that includes those data items plus the objective proof needed to accept the delivered product or service.

Evidence Return Package Contents (Generic)

Evidence return typically includes the CDRL and SDRL submittals, plus the supporting proof that ties them to the actual delivered configuration or performed service. A clean package contains:

- As-built/as-performed deliverable identification: serial/lot/work order/version so the proof ties to the exact delivered item or service instance

- Configuration baseline: drawings/spec revisions, BOM, software/firmware versions, and the approved change history

- Inspection and test results tied to acceptance criteria: test procedures used, pass-fail limits, results, and required signatures

- Certifications and traceability: material certs, CoCs, lot/heat traceability, and chain-of-custody where applicable

- Calibration references: equipment used, calibration status, and traceability to standards

- Nonconformance and deviation history: NCR dispositions, waivers/deviations with authorization numbers, and closure evidence

- Markings and rights compliance: correct data rights legends, markings consistency, and releasability checks

- Export and training evidence (if applicable): export logs, access lists, training completion, and handling procedures

- Cyber evidence (if applicable): attestations, tooling approvals, incident reporting proof, and boundary definitions

- Internal completeness checklist: signed confirmation that the package is complete, correct, and tied to as-built/as-performed reality

The key point is that evidence is progressive. It is built through gates, not assembled at the end.

Closeout: Finish Clean, So the Work Is Defensible Later

Closeout is where you protect margin and prevent the next dispute. Treat it like a phase gate, not an admin task you do after the team moves on.

Run a final acceptance gate with a checklist. The PM convenes a short, formal acceptance review and walks the evidence return checklist line by line. “Accepted” means the deliverable and the full evidence package are complete, correct, and tied to as-built/as-performed reality, with open NCRs, deviations, and approvals either closed or formally dispositioned. If it is not on the checklist, it is not done. If it is on the checklist and missing, do not accept.

Tie the final invoice to accepted deliverables, not effort. Finance invoices only against accepted milestones and references the acceptance identifier (deliverable ID, revision, and acceptance date). If acceptance is conditional, invoice only what was conditionally accepted and keep holdback tied to remaining evidence closure. This avoids “we billed it, now we have to argue about it.”

Lock down warranty and latent defect handling before you demobilize. Confirm warranty duration, response times, and who pays shipping, rework, and re-test in writing. Define the triage path: who receives the notice, who determines containment, who approves corrective action, and what evidence is required. If you do not define it now, the first post-acceptance failure becomes a contract fight.

Archive the evidence package like you expect an audit or a claim. Store it in a controlled repository with version control and retrieval metadata tied to serial/lot/work order, configuration baseline, and contract line item. Index it so a new PM can pull the full package in minutes, not days. If you cannot retrieve it, it does not exist.

Capture lessons learned and convert them into template changes. Do a short closeout review within days of acceptance while the facts are fresh. Record what clauses caused churn, what gates caught issues early, what evidence got rejected and why, and what metrics predicted trouble. Then update the subcontract templates, FCR fields, gate checklists, and KPI thresholds so, you do not relearn the same lesson on the next job.

Internal closeout meeting (typical): Run this as your supplier-side gate to make sure you are not about to trip over missing evidence, mismatched configuration, or open dispositions. The PM chairs it. Engineering, Quality, Config, Contracts, Documentation, Finance, and Logistics attend. Output is simple: “acceptance-ready” or “not ready,” plus a punch list with owners and dates.

Internal closeout meeting (typical): Run this as your supplier-side gate to make sure you are not about to trip over missing evidence, mismatched configuration, or open dispositions. The PM chairs it. Engineering, Quality, Config, Contracts, Documentation, Finance, and Logistics attend. Output is simple: “acceptance-ready” or “not ready,” plus a punch list with owners and dates.

Customer-attended closeout (use selectively) Internal gate first. Customer meeting only for required approvals, disputed items, or signature-level acceptance. Invite the customer when one or more of these are true:

- The contract defines a formal acceptance board, walkthrough, or joint acceptance event

- You need the customer to sign off on conditional acceptance, waivers, or final evidence format

- There were material changes, deviations, or interpretation decisions that you want closed cleanly on the record

- Customer review cycles are the critical path and you want to clear approvals live instead of through email

Best Practice That Keeps You Safe

Do an internal gate first. Do not put the customer in a meeting where you might discover gaps in real time. Once your package is clean, then a customer meeting becomes a fast “confirm and sign” event, not a scramble.

Closing

Customers do not buy effort. They buy accepted outcomes. If you treat flowdowns as requirements, plan them as work, assign them to owners, verify them through gates, and deliver them with an evidence return package, you stop negotiating at delivery. You get predictable acceptance, predictable cash flow, and audit-ready performance.

The alternative is the same every time: late clause discovery, documentation scrambles, stop-ship calls, disputed acceptance, and cash trapped behind “one more document.” That is preventable, but only if you build the system once and run it every project.

From a PMBOK Guide perspective, none of this is extra. It is standard project control applied to compliance: collect requirements, define scope, plan quality, plan and control procurements, manage stakeholder communications, and run integrated change control so the baseline stays defensible. The FCR is requirements traceability in operational form, readiness gates are quality control and scope validation checkpoints, and the evidence return package is what closes the loop for acceptance and closeout. When you run flowdowns this way, you are not doing “contract admin.” You are executing disciplined project management to deliver an accepted outcome that is usable, auditable, and payable.